There has been an ongoing debate regarding the reform, amendment, or rewriting of the constitution for quite some time. This debate primarily started with a comment by political scientist Professor Ali Riaz. On August 29, during a press conference at a hotel in the capital organized by the Center for Governance Studies (CGS), he said, “There is no way to amend the current constitution. One-third of the constitution is written in such a way that it cannot be altered. There are issues that, if not removed, you cannot do anything.”

When Professor Riaz made this statement, he had not yet become the head of the Constitution Reform Commission. Initially, the name of senior lawyer Dr. Shahdin Malik was announced as the head of the Constitution Reform Commission, but he expressed his inability to be a part of it. Later, in October, Ali Riaz was appointed as the head of the commission. This commission has already held discussions with various stakeholders and gathered their opinions. It has reviewed the constitutions of over a 100 countries, as well as the events before and after each amendment to Bangladesh’s Constitution since 1972. They are expected to submit their report with recommendations on constitutional reform to the government by January.

The Constitution of Bangladesh has a total of 153 sections, including many clauses and sub-clauses. At the beginning of the constitution, there is a preamble, and at the end, there are annexes containing the historic speeches, such as the March 7 speech of Bangabandhu, his declaration of independence on early March 26, 1971, the independence proclamation issued by the Mujibnagar government on April 10, 1971, and the oaths and declarations of various positions.

It is expected that the Constitution Reform Commission will provide observations, opinions, and recommendations on each issue; however, the submission of these recommendations does not mean that the constitution will be changed automatically. In fact, according to the provisions of Bangladesh’s current constitution, even a small change, such as altering a comma or a semicolon, requires the approval of two-thirds of the members of Parliament.

Another way for constitutional reform or rewriting is through the formation of a Constituent Assembly. In other words, the upcoming 13th national election could be held to form a Constituent Assembly, and many believe that constitutional reform, amendment, or rewriting should take place within that assembly. Even the Commission’s head, Professor Ali Riaz, holds this view. However, to form a Constituent Assembly, political consensus is needed. Particularly after the fall of the Awami League, it is currently impossible to form such an assembly without the approval and support of the country’s major opposition party, the BNP. Therefore, the recommendations provided by the Constitution Reform Commission can be approved in the next Parliament, only if there is political consensus on them.

Therefore, it is difficult to say at this point exactly where changes will occur in the constitution and through which process they will be made. However, it is clear that there are many provisions in Bangladesh’s current constitution that are contradictory and favorable to the development of authoritarian rule. One such provision is the fluctuation between state religion and secularism. Although it is difficult to say with certainty what the Constitution Reform Commission will recommend on this issue, it can be speculated that they will recommend reforms to the contradictory provision that declares Islam as the state religion while upholding the principle of secularism.

How the state religion came about:

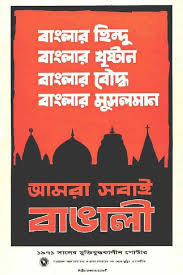

In fact, one of the key issues in Bangladeshi politics has been the discussion and debate over “state religion.” In the year following Bangladesh’s independence, the constitution adopted by the Constituent Assembly on November 4, 1972, did not mention a state religion. Instead, one of the core principles of the constitution was “secularism.” Even though a member of the constitution drafting committee, A.K. Mosharraf Hossain Akand, proposed including the phrase “In the name of the Almighty, the Most Compassionate, the Most Merciful” in the preamble, it was not accepted. However, within a few years, the phrase “Bismillah” was added to the preamble, and the provision regarding the state religion was incorporated through the 8th amendment.

In 1978, during Ziaur Rahman’s rule, the second schedule of Presidential Order No. 4 included the phrase “Bismillahir-Rahmanir-Rahim” (In the name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful) into the constitution. This was legalized the following year through the 5th amendment of the constitution, which was adopted on April 6, 1979. Thirty-two years later, in 2011, an attempt was made to return to the original 1972 constitution through the 15th amendment, but the phrase “Bismillah” was not removed from the preamble. However, there was a slight change in its translation. The preamble now reads: “Bismillahir-Rahmanir-Rahim” (In the name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful), in the name of the Supreme and Compassionate Creator.

The second article of the original 1972 constitution dealt with the national boundaries of the republic. However, in 1988, President Hussain Mohammad Ershad introduced the 8th amendment to the constitution, adding a new Article 2A, which declared Islam as the state religion. It stated: “The state religion of the Republic is Islam, but other religions may also be practiced in peace in the Republic.”

Why the provision could not be abolished:

Even during the 15th Amendment in 2011, the provision declaring Islam as the state religion was not abolished. However, some amendments were made to the article. The sentence now reads: “The state religion of the Republic is Islam, but the state shall ensure equal status and equal rights for the practice of Hinduism, Buddhism, Christianity, and other religions.” In other words, while the state religion was not abolished, this amendment ensured that Islam and other religions would be treated equally, and it guaranteed equal rights for everyone to practice their religion. However, there is ongoing debate about whether declaring a state religion can truly guarantee equal status and rights for other religions.

It is noteworthy that for the 15th Amendment of the Constitution, a special committee of 15 members was formed on July 21, 2010, chaired by the then Deputy Leader of Parliament, Syeda Sajeda Chowdhury, and co-chaired by Suranjit Sengupta. This committee gathered the opinions of political parties and key figures of the state on various constitutional amendments. As the leader of the ruling party, Sheikh Hasina also explained her party’s stance on the issue of state religion during a press conference at the Ganabhaban on April 27, 2011. When asked about her party’s position on the state religion, she stated, “Only people can have their own religions, the state should not have any religion.” She also referred to Hussain Mohammad Ershad, implying that those who are not truly engaged in religion often talk the most about it. She acknowledged, however, that religion stirs strong emotions among people. Therefore, the issue of the state religion could not be removed from the constitution. She further explained that her party had proposed maintaining Islam as the state religion while ensuring that Hindus, Buddhists, Christians, and followers of other religions could equally enjoy the right to practice their faith.

Sheikh Hasina pointed out that the state religion was added to the constitution through an undemocratic, one-party election in 1988, and she believed that it was not justified and should not have been done. (Amin Al Rasheed, The Fifteenth Amendment of the Constitution: Discussion and Debate, Oitijhyo/2011, p. 64).

It is said that Ershad, through the 8th Amendment, sought to achieve two objectives: first, to gain the support of the religiously devout majority of the country by invoking the name of Islam, and second, to weaken his main political opposition by decentralizing the judiciary. Ershad’s government had been struggling with legitimacy from the very beginning. The crisis of legitimacy was intense, and his government had escalating conflicts with opposition parties. It can be argued that, at a point when Ershad’s government was on the brink of being ousted through a popular uprising, he needed to take actions that would regain some public sympathy and support. (Kazi Zahed Iqbal, Bangladesher Sangbidhan Sangshodhoni: 1972-1998 Prekshapot o Porjalochona, Dhruvopod/2016, p. 85).

In 1988, when the bill for the 8th Amendment related to state religion was introduced in Parliament, it sparked significant controversy. For example, Nurul Islam Moni, an independent member of Parliament from the Barisal-2 constituency, opposed the 8th Amendment, calling it an “attempt to gain political advantage.” He strongly criticized the government, stating, “In a country where 95 per cent of the population are Muslims, declaring Islam as the state religion is unnecessary and is just a political move. This could be declared any morning that Islam is the state religion, and we already follow it. I do not believe anyone will oppose this, but this is an attempt to gain political advantage.” Moni further said, “Although Jamaat supports this, we see that the Awami League does not support it, and the BNP is somewhat neutral. This is creating discord. Communal harmony is being disturbed, and there is an attempt to create communal riots through this bill.” In this context, Nurul Islam Moni also called on the members of the Jatiya Party to join the Jamaat-e-Islami. (National Assembly Proceedings, 1988).

Moslem Uddin, the Member of Parliament from Rajbari-2 elected by the Combined Opposition Parties, said, “A religion cannot be imposed upon anyone. One cannot be made to believe, nor can anyone be forced to pray, fast, perform Hajj, or give Zakat. These are all spiritual needs of an individual, and people follow a religion based on their desire for divine peace, which is often influenced by the religion of their ancestors. Therefore, I believe that declaring Islam as the state religion will not make people pray more, nor will it lead to the construction of more mosques and madrasas.”

The strongest and longest speech against the state religion bill was delivered by the opposition leader, ASM Abdur Rob. He said, “Reciting ‘Bismillahir Rahmanir Rahim’ and slaughtering a pig will not make it halal. In this Parliament, there is a member who wears a topi and sits on the Treasury Bench, who has performed Hajj several times. I have heard from Haji Abdul Odu, that during the Pakistan era, there was a drug store in a district town called ‘Swadeshi Medicine Shop,’ and under it, it was written that foreign liquor was available.

Fifteen distinguished individuals filed a writ petition in the High Court, challenging the legality of adding the state religion provision to the constitution. Twenty-three years later, on June 8, 2011, a bench of Justices A.H.M. Shamsuddin Chowdhury and Gobinda Chandra Thakur issued a rule. On the same day, 14 senior lawyers were appointed as amici curiae. Almost five years later, on March 28, 2016, the writ petition was directly dismissed by a High Court bench comprising Naima Haider, Qazi Reza-ul-Haque, and Mohammad Ashraful Kamal. Eight years later, on April 25, 2024, a full verdict of 52 pages was published, stating: “Declaring Islam as the state religion does not violate the fundamental structure of the constitution.”

Fifteen distinguished individuals filed a writ petition in the High Court, challenging the legality of adding the state religion provision to the constitution. Twenty-three years later, on June 8, 2011, a bench of Justices AHM Shamsuddin Chowdhury and Gobinda Chandra Thakur issued a rule. On the same day, 14 senior lawyers were appointed as amici curiae. Almost five years later, on March 28, 2016, the writ petition was directly dismissed by a High Court bench comprising Naima Haider, Qazi Reza-ul-Haque, and Mohammad Ashraful Kamal. Eight years later, on April 25, 2024, a full verdict of 52 pages was published, stating: “Declaring Islam as the state religion does not violate the fundamental structure of the constitution.”

The Negative Consequences of State Religion:

The question is, what has happened by maintaining the contradictory position of declaring Islam as the state religion while upholding secularism as a constitutional principle, and why did the highest court not annul this provision? Has the presence or absence of a state religion in a country’s constitution influenced the religiosity of its people? Is it true that before declaring Islam as the state religion, the people of Bangladesh were less religious, and after the declaration, they became more religious?

Rather, declaring a state religion means constitutionally making the followers of other religions second-class citizens. Since the majority religion is declared the state religion, the followers of other religions are relegated to the status of minorities. This leads to the arrogance of the majority and the marginalization of the minority, creating divisions among the people living in the state.

The question arises after the political changes on August 5, and the subsequent allegations of attacks on the Hindu community in various parts of the country. While not all of these accusations may be entirely true, and some media outlets in neighboring India may have exaggerated or sensationalized the issue, there are undeniable realities. Specifically, during the last Durga Puja celebrations, Hindus in many parts of the country faced insecurity, and their distress was exacerbated by overenthusiastic actions of local political parties and religious groups claiming to provide protection. One religious party even announced that it would guard Hindu temples and idols, raising the question: in a country whose constitution’s principle is “secularism,” why is there a need to guard temples when mosques and churches do not require similar protection?