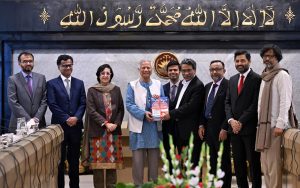

The reform commission handed over the report to Chief Adviso Dr. Yunus on January 15th, 2025

The Constitutional Reform Commission has recommended equality, human dignity, social justice, pluralism, and democracy replacing nationalism, democracy, socialism, and secularism.

In the declaration of independence issued on April 10, 1971, it was stated that equality, human dignity, and social justice would be ensured for the people of Bangladesh. These three principles are considered the original fundamental principles of Bangladesh’s Constitution. The Constitutional Reform Commission has recommended adding a new term, “pluralism,” to the current constitutional principle of “democracy,” while retaining these three principles.

Before discussing how or through what process the fundamental principles of the Constitution will be changed, or whether political consensus can be reached on this matter, let’s take a step back. The debate over the fundamental principles of the Constitution actually began in 1972 in the Constituent Assembly. Apart from “democracy,” the remaining three principles were the subject of intense debate in the Assembly. There were also some unintended incidents regarding Bengali nationalism, the effects of which are still felt today.

On March 25, 1971, when the Pakistani invading forces began committing genocide, the armed struggle for liberation, the Liberation War, began the following day. For nine months during the war, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was imprisoned in Pakistan. In his absence, the war was led by the interim President Syed Nazrul Islam and Prime Minister Tajuddin Ahmed, with Mujib being declared president.

For the legal legitimacy of Bangladesh and its global recognition, it was essential to form a government. This required the creation of a Proclamation of Independence. The document was drafted by Barrister Amir-ul Islam. He wrote, “Tajuddin Bhai and I used to stay in a small room, and I did the writing work under the light of a table lamp. I had no books, and there was no copy of other countries’ declarations of independence. I had read the American Declaration of Independence long ago. The original document was floating in front of my eyes, and I could remember the large signatures, but I couldn’t recall the language or form. However, I didn’t try too hard to recall. I just focused on the context in which we had the right to declare our independence.” With that thought, he drafted the first version of the declaration, specifying the powers of the interim president for declaring independence.

After drafting the Proclamation of Independence, I showed it to Tajuddin Bhai. He liked it. I said, “We are all now engaged in war. It would be better if we could show this draft to an experienced lawyer.” He replied, “Who will we find at this moment? If possible, show it to someone.” In the meantime, lawyers from the Kolkata High Court had expressed their support for our liberation war. Among them, I had heard the name of Subrata Roy Chowdhury, who had international recognition. I thought I had read some of his articles. I obtained his address through the BSF and contacted him by phone, requesting to meet him. He agreed. His house was in Ballygunge (Kolkata). I introduced myself as ‘Rahmat Ali.’ When I reached Subrata Roy Chowdhury’s house, I showed him the draft of the declaration that I had prepared. Upon seeing it, he leaped with joy and asked if I had written it. I confirmed with a yes. He said, “There’s no need to change even a comma or semicolon.” (Barrister Amir-ul Islam, Memories of the Liberation War, Kagoj Prokashon/1991, p. 49).

The declaration read: “We hereby proclaim the establishment of Bangladesh as a sovereign People’s Republic, in order to ensure equality, human dignity, and social justice for the people of Bangladesh.” This Proclamation of Independence is considered the basic document of Bangladesh’s Constitution and is regarded as the source of the three rights mentioned—equality, human dignity, and social justice—forming the original principles of the Constitution. It was naturally expected that these principles would be included in the Constitution drafted after the country’s independence. However, this did not happen. Nonetheless, it is true that the principles of equality, human dignity, and social justice align closely with many aspects of the Constitution’s four fundamental principles. For example, Article 11 of the Constitution states that the Republic will be a democracy where fundamental human rights and freedoms are guaranteed, respect for human dignity and value will be ensured, and effective participation through elected representatives will be guaranteed at all levels of administration.

Where there is democracy, there is equality. Equality cannot exist without democracy, and democracy cannot exist without equality. To ensure human dignity, there must also be a democratic environment in the state. Human dignity means that every individual has personal autonomy and freedom, and every person has the right to equal dignity and rights—this is the spirit of democracy.

Social justice is also linked to democracy. In an undemocratic society, justice does not exist. This means that when a state genuinely establishes democracy, equality, human dignity, and social justice are automatically realized. As a result, some people believe that simply having democracy as the fundamental principle of the Constitution is enough. There is no need to separately mention socialism, nationalism, or secularism. For example, Abul Mansur Ahmed wrote: “Without democracy, everything else is just government policy, not national policy. Once democracy is properly established in the country, everything else, the good things, will follow automatically. The good things mean those that are in the interest of the people, which will be done according to the people’s wishes. Nationalism, socialism, and secularism all exist for the people and are therefore beneficial for a democratic state. Unrestricted democracy guarantees this welfare. If democracy is not secure, none of these things are secure.” (The Fifty Years of Politics I Have Seen, Khoshroz Kitab Mahal/2010, p. 619).

In fact, regarding the fundamental principles of the Constitution, Bangabandhu clarified his position early on, on January 13, 1972. This was two days after he took the oath of office as Prime Minister, and it was his first press conference in the newly independent country. He said, “The transition to socialism will be through democratic means.” A few days later, on February 6, 1972, Bangabandhu went on a state visit to India, which was his first foreign trip as the Prime Minister of Bangladesh. There, he highlighted the four fundamental principles of the Constitution, including democracy. On February 26 of the same year, at a public gathering in Sirajganj, he stated, “I have written in the constitution that the exploiters will never be able to exploit the people of Bengal again, Inshallah. Secondly, I believe in democracy. The people’s representatives, elected by the people’s vote, will run the country, and no one else should interfere. Thirdly, I am a Bengali. I want to live with honor as a Bengali nation. Fourth, my state will be secular. That means not anti-religion. A Muslim will follow his religious practices, a Hindu will follow his, and a Buddhist will follow his. No one can obstruct anyone else. However, one thing is clear: business will no longer be allowed in the name of religion.” (Timeline of Bangabandhu, Shilalipi/2021, p. 260)

At the time of making these statements, the Constitution Drafting Committee had not yet been formed. This means that Bangabandhu had already been thinking about what the fundamental principles of the Constitution would be, and he mentioned, “I have written in the constitution.” This implies that a draft of the Constitution may have already been in his mind, which was later formally prepared under the leadership of Dr. Kamal.

Bangladesh parliament house

On April 10, 1972, the Constituent Assembly meeting began, and the next day, a 34-member committee was formed, chaired by the renowned lawyer Dr. Kamal Hossain, to prepare the draft of the Constitution. On October 12, when the committee submitted its report, detailed discussions took place on each article. Among the four fundamental principles, there was intense discussion and debate on the three principles other than democracy. Senior leaders like Bangabandhu, Syed Nazrul Islam, and Tajuddin Ahmed strongly advocated for these principles.

It cannot be denied that although a 34-member committee worked on drafting the Constitution and there was a lengthy discussion on the Constitution Bill in the Constituent Assembly, Bangabandhu’s direct guidance was present throughout the entire process. In the face of his towering personality, others were outshined. Therefore, it was highly unlikely that anything deviating from his wishes would have been accepted.

Bangabandhu’s vision for the state was democracy in politics, socialism in economics, nationalism in foreign policy, and secularism in society. Although democracy and socialism are distinct forms of government, Bangabandhu sought to harmonize these two principles. His dream was to achieve socialism through democratic means.

It is often said that the inclusion of socialism as a fundamental principle in the Constitution was influenced by Bangabandhu’s relationship with Russia, which had supported Bangladesh during the Liberation War. A month before the Constitution Drafting Committee was formed, on March 1, 1972, Bangabandhu visited Russia.

Similarly, the inclusion of secularism as a fundamental principle in the Constitution is believed to have been influenced by India. Furthermore, several members of the Constituent Assembly mentioned in their speeches that the principle of secularism was added based on the experience of Pakistan’s religious-based state structure. Their main argument was that Pakistan had used religion as a pretext to carry out genocide in Bangladesh in 1971. Therefore, to prevent religion from interfering with the governance of Bangladesh, secularism was included as a fundamental principle in the Constitution.

Dr. Kamal Hossain, head of the Constitution Drafting Committee 1972

In 1972, when Bangladesh’s Constitution was drafted, the phrase Bismillah was not included at the beginning. Although a member of the Constitution Drafting Committee, AK Mosharraf Hossain Akand, proposed adding “In the name of the Almighty, Most Gracious, Most Merciful” at the beginning of the preamble, Bangabandhu did not approve of it. However, during Ziaur Rahman’s time, with the Fifth Amendment, Bismillah was added to the preamble. Later, during the Ershad government, the Eighth Amendment introduced Islam as the state religion in the Constitution. This led to a contradiction, as the Constitution simultaneously maintained Bismillah, Islam as the state religion, and secularism as a fundamental principle — creating a kind of cooking up.

In 2011, during the Fifteenth Amendment, many provisions of the original 1972 Constitution were restored, but the Awami League government did not have the courage to remove Bismillah or the state religion from the Constitution. Additionally, there was a ruling from the higher courts on this matter. However, during this amendment, a slight revision was made to the article on state religion. The revised wording now reads: “The state religion of the Republic is Islam, but the state shall ensure equal status and equal rights in the practice of Hinduism, Buddhism, Christianity, and other religions.” This change ensures that while the state religion remains Islam, other religions are given equal status, and the right to practice all religions is guaranteed. However, there remains ongoing debate about whether declaring one religion as the state religion can ensure equal status and rights for other religions.

The Constitutional Reform Commission’s recommendation to remove secularism from the fundamental principles of the Constitution may potentially end this contradiction. However, if Bismillah and the state religion are retained, the situation will remain unchanged. This is because when one religion is constitutionally recognized as the state religion, other religions are often marginalized. Perhaps, this is why the Constitutional Reform Commission has suggested adding “pluralism” (bahuttabad) as a new principle in the Constitution.