It is noteworthy that during the Liberation War of 1971, the Proclamation of Independence issued on April 10 served as an inspiration for the “Proclamation of the July Revolution.” This agenda was introduced by the Anti-Discrimination Student Movement and the National Citizens’ Committee at an event held at the Central Shaheed Minar on December 31.

The organizations stated that the “July Proclamation” would serve as the “declaration for the future of Bangladesh,” and that it would render the ousted Awami League “irrelevant,” likening it to the “Nazi regime.” Additionally, the proclamation aimed to “bury” the 1972 “Mujibist” Constitution.

Shafiqul Alam, The Chief Advisor’s Press Secretary

A draft of the proclamation, which was rumored to be read on that day, was leaked on social media two days prior. However, the situation changed drastically the night before the event. Initially, the Chief Advisor’s Press Secretary, Shafiqul Alam, claimed that the government had no involvement in this program and that it was a private initiative. However, at an emergency press briefing on December 30, he announced that the interim government would draft such a proclamation with political consensus.

The Chief Advisor’s Press Wing issued a written statement on the matter:

“On behalf of the interim government, an initiative has been undertaken to draft a proclamation of the July Uprising based on national consensus. The proclamation will reflect the unity of the people forged through the July Uprising, the anti-fascist spirit, and the desire for state reform. It will be prepared with input from all participants of the uprising, including the Anti-Discrimination Student Movement and other political parties. The proclamation will outline the context of the uprising, the basis of unity, and the aspirations of the people. We hope that with everyone’s participation, this proclamation will be finalized unanimously and presented to the nation soon.”

Initially, the Chief Coordinator of the Anti-Discrimination Student Movement announced that the December 31 program would proceed as planned. However, at midnight, it was declared that the proclamation would not be read at the event. The program was renamed “March for Unity.” During the event, the government was given a 15-day deadline to issue the July Proclamation.

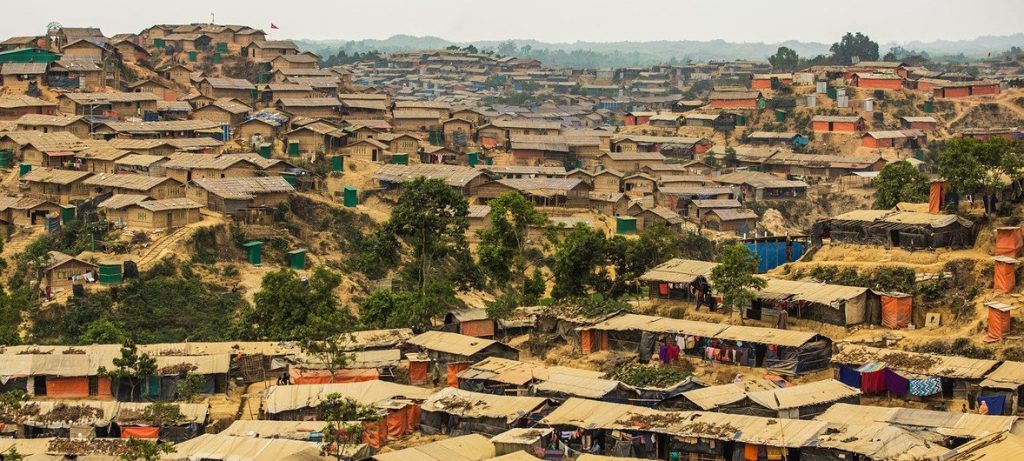

March for Unity, December 31, 2024

Subsequently, Advisor Mahfuz Alam stated that the government would not draft the proclamation but would facilitate the process. Nonetheless, it was announced that the government would meet with political parties on this matter. However, as detailed earlier, the so-called “all-party meeting” left much to be desired.

Questions arose about whether sending last-minute invitations via text messages—allegedly from an advisor’s phone or an unknown number—had disrespected political parties. This raised concerns about how serious the government was about the proclamation or whether it had taken a middle-ground stance under pressure from key stakeholders like the Anti-Discrimination Student Movement and the National Citizens’ Committee. People also questioned whether the involvement of political parties and their opinions was merely a formality.

A larger question looms: Did the January 16 “all-party meeting” achieve any political consensus on the July Proclamation, despite the Chief Advisor’s repeated emphasis on it? Evidence suggests otherwise, as demonstrated by a text message sent by the Chief Advisor’s Press Wing on Saturday morning:

“Following the all-party dialogue on the July Proclamation last Thursday, feedback is being collected from all stakeholders, including political parties that participated in the uprising. You may send your considered opinions via letter to Advisor Mahfuz Alam at the Chief Advisor’s Office. Opinions will be accepted until January 23. These will be reviewed to draft a revised and widely accepted proclamation, which will be announced publicly without delay.”

Asif Nazrul, Advisor of the interim government

Details of the opinions expressed by political parties regarding the July Proclamation during Thursday’s meeting were not made public. However, following the meeting, Law Advisor Professor Asif Nazrul told reporters, “There is no disagreement among political parties on the July Proclamation. Everyone agrees to issue it, no matter how much time it takes. However, they have cautioned against unnecessary delays.” He also mentioned a proposal to form a committee to discuss the proclamation with everyone.

It is evident that political consensus on the July Proclamation has yet to be achieved. Moreover, there appears to be a tug-of-war between the interim government and the Anti-Discrimination Student Movement and the National Citizens’ Committee on this issue. As a result, uncertainty looms over the future of this proclamation. Particularly if, as Advisor Mahfuz Alam indicated, the government ultimately only “facilitates” the process, there are lingering questions about whether the final document will be widely accepted, whether it will incorporate the views of all parties, what its language will be, and, most importantly, what the benefits of drafting such a proclamation will be for the interim government, the country’s politics, and the people.

The hand written copy of constitution of Bangladesh, 1972

A draft of the proclamation, which has already been published in the media, references liberation from colonial rule in 1947, independence through a people’s war in 1971, and subsequent events. It states that the 1972 Constitution failed to reflect the aspirations of the martyrs and participants of the Liberation War. Subsequent administrations also failed to build state and institutional structures effectively, ensuring neither democracy, the rule of law, nor accountability of the ruling class.

The draft further mentions that political failures to ensure the proper transfer of power paved the way for conspiratorial events like the “1/11” transition, which solidified Sheikh Hasina’s dominance. It criticizes her tenure for enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, constitutional amendments serving partisan interests, and the destruction of state and social institutions. Additionally, it claims that her regime’s authoritarianism and human rights abuses have tarnished Bangladesh’s international reputation.

The draft also highlights corruption, bank looting, and economic destruction under Sheikh Hasina’s family-led regime, which has drained the country of its potential. It acknowledges the relentless struggles of political parties, students, and labor organizations over the past 15 years against oppression, enforced disappearances, and extrajudicial killings. The draft accuses the Awami League of suppressing legitimate movements with brutality while serving the interests of foreign states.

While there may be political consensus on corruption and plundering under Sheikh Hasina’s regime, the claim in the draft that “the 1972 Constitution failed to reflect the aspirations of the martyrs and participants of the Liberation War” might not garner unanimous support. The 1972 Constitution did embody the hopes and aspirations of the martyrs and freedom fighters, and its gradual degradation into a tool for power retention was a result of political misuse rather than inherent flaws in the Constitution itself.

Salahuddin Ahmed, Senior leader of BNP

Another significant issue is the title of the proclamation: “Proclamation of the July Revolution.” Several political parties, including the BNP, who were active participants in the July uprising, do not view it as a “revolution.” If it is not a revolution—rather a significant political movement or uprising—then the rationale for drafting a proclamation becomes questionable. The fundamental differences between a revolution and an uprising make it clear that recent events in Bangladesh do not qualify as a revolution. Even individuals close to the government admit this. If the movement cannot be classified as a revolution, questions will arise about the justification for the proclamation, leading to potential discord among political parties.

This raises a critical question: if a proclamation is eventually drafted, will it merely remain a document, or will it serve as a foundation for charting the course of Bangladesh’s future? A second question is whether, given the current state of the economy, law and order, and widespread disarray in the state under the interim government over the past five months, the July Proclamation is even necessary or relevant at this moment.

To resolve the country’s ongoing crises, curb corruption, and prevent such issues permanently, the priority should be institutional reforms and the transfer of power to an elected, credible, and accountable political government through free, fair, and trustworthy elections. Political parties, as well as the proponents of the July Proclamation—the Anti-Discrimination Student Movement and the National Citizens’ Committee—should fully support the government in achieving this critical objective.

Published: The Daily Star, January 18, 2025