In Bangladesh’s existing electoral system, governments are typically formed by a “minority” of voters, and even in local government elections, the winners often lack the support of the majority—evidenced most recently by the two Dhaka City Corporation elections.

In Dhaka North City Corporation, the Awami League’s candidate, Atiqul Islam, became mayor with the support of only 14.84% of total voters. In Dhaka South, Sheikh Fazle Noor Taposh became mayor with just 17.30% voter support. According to the Election Commission, voter turnout was 25.30% in the North and 29% in the South. This means that approximately 75% of voters in the North and over 70% in the South did not vote. Moreover, not all those who voted chose Atiqul or Taposh.

Atiqul Islam and Sheikh Fazle Noor Tapash, formar Mayor of Dhaka City Coprporation

Since the current electoral system does not set a minimum percentage of votes required for victory, anyone can become a public representative with the mandate of just 10% of voters. At the same time, there is no constitutional or legal provision to challenge such elections. Therefore, while Atiqul Islam received only 14.84% of votes in Dhaka North, leaving 85.16% uncast or against him, and Fazle Noor Taposh received just 17.30% in Dhaka South, leaving 82.70% uncast or against him, it cannot be claimed that these percentages represent rejection. Voting is a citizen’s right, but choosing not to vote or abstaining from voting is also their right.

Before the Ninth National Parliament Election, the Representation of the People Order (RPO) was amended to include a provision for a “No” vote, allowing voters to express disapproval of all candidates if they didn’t support any. However, the government formed after that election abolished this provision. This means there is no longer an option for a “No” vote. If the “No” vote provision had remained, it would have been possible to gauge the percentage of voters who lacked confidence in the competing candidates. As this percentage grew, political parties would likely have been more cautious in nominating candidates.

However, since significant financial transactions and calculations, including considerations of family ties, influence candidate nominations at both national and local levels, the “No” vote provision might have created psychological pressure on political parties. It is likely this consideration led to its abolition.

The question now is: why are people losing interest in voting? Various explanations have been offered. Some influential government ministers have even claimed that people didn’t vote because they are living in “peace and happiness.” How many believe this theory is a matter for research. However, the primary reason for low voter turnout is likely the belief that the election outcomes are pre-determined. Naturally, people won’t go through the trouble of attending a game whose result they already know. But this article does not focus on that issue. Instead, it seeks to examine how governments are formed by minorities and how representatives are elected without the support of the majority.

In the Second National Parliament Election in 1979, the BNP formed the government with 41.2% of the votes. In the Third National Parliament Election in 1986, the Jatiya Party won with 42.34%. In the Fifth National Parliament Election in 1991, the BNP won with 30.81%. In the Seventh National Parliament Election in 1996, the Awami League came to power with 37.44%. In the Eighth National Parliament Election in 2001, the BNP secured government formation with 41.40% of the votes.

After the country’s independence, the first parliamentary election in 1973 naturally resulted in a landslide victory for the Awami League, which had led the Liberation War. In that election, they won 293 out of 300 seats, receiving 73.20% of the votes. Beyond this, only one seat each was won by JASAD and the Bangladesh National League, with five independent candidates. Notably, while JASAD received 6.52% of the votes and secured one seat, NAP (Mozaffar) received 8.33% but didn’t win any seats.

The elections of 1991, 1996, 2001, and 2008 are often regarded as relatively fair elections in the country’s history. In the 1991 election, the BNP secured 140 seats with 30.81% of the vote, while the Awami League, with just 0.73% fewer votes (30.08%), won only 88 seats. In other words, the difference in vote share was less than 1%, but the difference in seats was 52. Additionally, in the same election, the Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League (BKSAL) won 5 seats with 1.81% of the vote, while the Zaker Party, despite receiving 1.22% of the vote, did not secure a single seat. This discrepancy arose because the Zaker Party contested in 251 constituencies, whereas BKSAL fielded candidates in only 68.

In the June 12, 1996 election, the vote share difference between the Awami League and BNP was just 3.84%. However, the difference in seats was 30, with the Awami League securing 146 seats and the BNP 116.

In the 2001 election, the vote share difference between the Awami League and BNP was only 1.38%. Yet, the BNP won 193 seats, while the Awami League secured just 62. If the distribution of seats were proportional to the vote share, the number of seats for both parties would have been nearly equal—almost a 50-50 split. However, under the existing electoral system, even a small difference in popular votes translated into a massive disparity in seat allocation.

The most peculiar outcome of this system occurred in the 2008 election. In that election, the Awami League won 230 seats with 49% of the vote, whereas the BNP, with 33.2% of the vote, won only 30 seats. If seats were allocated based on proportional vote share, the BNP would have received significantly more seats in the 2008 election.

In our country, the current electoral system is called the First Past the Post (FPTP) system. This means that the candidate who receives the highest number of votes (even if it’s just one vote more than their closest competitor) is declared the winner, while all other candidates lose.

One major drawback of this system is that it fails to ensure participation from all segments of society. Since the winner is solely determined by receiving the most votes, various irregularities, manipulations, and unethical practices often take place to secure victory. When individual victory becomes the primary focus, representation of marginalized or underprivileged communities is often overlooked. This system also allows for the possibility that a party with fewer overall or popular votes than its rival can still form the government by winning more constituencies.

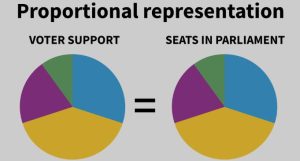

For this reason, many countries around the world have adopted the Proportional Representation (PR) system. In this system, parties, rather than individual candidates, contest the election. Based on the total votes a party receives nationwide, they are allocated seats in parliament proportionately. This ensures that every vote counts and that even parties receiving fewer votes have representation in parliament. In our parliament, the allocation of reserved women’s seats is done proportionally. That is, the 50 reserved seats are distributed among parties in proportion to their representation in parliament, even though the general election follows a different method.

Under the PR system, each party submits a candidate list to the election commission, ensuring representation from all levels of society. This list is kept confidential. Based on the percentage of votes a party receives, representatives are chosen from this list in order of priority. For instance, in a 300-seat parliament, if a party receives 1% of the votes, they would be entitled to 3 seats proportionally. A government would then be formed by the party or coalition of parties that secures 51% of the total votes. If no single party achieves this majority, multiple parties can form a coalition to govern. In this system, voters cast their votes for a party, not an individual candidate. As a result, parliament would include representatives from large, medium, and small parties alike, reducing the dominance of powerful individual candidates.

In the current FPTP system, parties nominate candidates for each constituency based on their likelihood of winning, by any means necessary. Consequently, nominations are often given to the most “strong” candidates, regardless of their acceptance within the party or community, their connections with the public, their education, or their values. Instead, candidates are chosen based on their perceived ability to win the election at any cost, as determined by the party’s leadership.

In this system, as winning requires just one vote more than the nearest competitor, candidates go to great lengths to secure even that one extra vote, often resorting to various forms of malpractice and misuse of power. This is one of the primary reasons why politics in the country has essentially devolved into a two-party system, with people’s choices in national elections limited to the “Boat” (Awami League) and the “Sheaf of Paddy” (BNP). However, proportional representation voting would mitigate this unhealthy competition. When people vote for a party instead of an individual, local-level conflicts would decrease. A party receiving over 50% of the vote would naturally dominate the parliament, but even a party securing 10% of the vote would have representation. This would create a truly multiparty parliament.

Under the current electoral system, however, parliament essentially becomes a one-party body, with occasional strong opposition. Most other parties remain outside parliament, even though they garner some votes. This means that the opinions of voters who supported these smaller parties hold no value in the existing system.

Since our parliament is unicameral, there is no provision to select representatives from educated or marginalized sections of society through indirect elections. Yet neighboring countries like India and even Nepal have systems ensuring representation from all levels of society. Therefore, it is time to rethink the idea of a unicameral parliament.

In addition to introducing proportional representation, it is also necessary to eliminate the provision for uncontested elections. Article 65(2) of the Constitution states:

“The Parliament shall consist of three hundred members to be elected in accordance with law from single territorial constituencies by direct election.”

Direct election implies that competition is mandatory. However, according to the Representation of the People Order (RPO), if there is only one candidate in a constituency, that candidate can be declared elected uncontested. Regardless of the legal interpretation, this is not democratic by any means.

It is worth recalling that before the 10th National Parliamentary Election on January 5, 2014, the High Court issued a rule on December 17, 2013, questioning why Section 19 of the RPO, which allows uncontested elections, should not be declared unconstitutional. This was in response to a writ petition filed by Khandaker Abdus Salam, Vice-Chairman of the Jatiya Party. However, after concluding arguments, the court dismissed the petition on June 19, 2014, stating that the provision was not in conflict with the Constitution.

Nonetheless, introducing proportional representation in elections would automatically eliminate such controversies. It is also expected that debates surrounding election-time governments—whether interim, caretaker, or transitional—would also come to an end under this system.

This discussion pertains to national elections. In the case of local government elections, there is no scope for proportional representation. However, a recall system should be introduced here. Citizens should have a constitutional right to remove their representatives at any time if they feel they have failed to fulfill their promises or address problems. Currently, the government can remove any representative at any time, but this is usually done for political reasons. There is no precedent of a representative being removed in the public interest.

Moving beyond these debates, it is crucial to investigate why people are losing interest in going to polling stations and to identify the failures of the state, political parties, and other stakeholders in this regard. Politicians themselves must find a way out of this crisis. Otherwise, the future of the country’s electoral system may be in jeopardy.